Hey hey 👋,

If you live in a major city or a big college town, you probably have gotten flyers from one of those delivery companies that promise to deliver groceries or household goods in under 30 mins. I remember first seeing those ‘instant commerce’ flyers a few years back in Ann Arbor.

I never paid much attention to the space until a couple of years ago, when I interviewed David Lin, the CEO of Duffl, a GoPuff competitor focusing on college campuses. They hire students to deliver snacks and most convenience store items in under 10 mins on scooters. Duffl’s insane speed is the direct result of having supply close to the customers. Their secret sauce is their ability to turn any space into a micro fulfillment center (MFC), including apartments. Due to this proximity to demand, their racers can deliver up to 20 orders an hour which dwarfs Postmates and DoorDash’s 2-3 orders per hour. They were making $33K in monthly revenue six months after inception.

In addition, the way they store inventory is dynamic and flexible. They curate hundreds of items based on customer demand data.

“So the problem we have to solve is basically how do we know what customers want? How do we know how much of it to buy? How do we evaluate products individually on a performance basis? And how do we implement all that data into our platform so that customers feel like they are getting recommended the best products available? It becomes a very complicated branching problem.” - David, CEO of Duffl

When I moved to San Francisco this past year, I started using an instant commerce app, Food Rocket. It started as an experiment due to their attractive intro discounts but now I only order groceries from this app. They fundamentally changed how I view grocery shopping.

Before the pandemic, I shopped in person at local grocery stores. When the pandemic started, I pivoted to Amazon Whole Foods and Instacart. I was happy about the selection and the ease but it was not really on-demand. Sometimes, I had to buy days in advance to book a delivery time slot. To cope with this, I usually only ordered a massive amount of grocery items every other week to make sure I had enough supply to last me a while. Now, after getting hooked on those instant commerce platforms, I am ordering almost 3 times a week (though much smaller orders), often 30 mins before I start cooking.

Many venture investors took notice of this new consumer behavior and poured significant amounts of money into some of the leading players. If instant commerce players continue to grow with strong unit economics, I believe this industry could take the majority share of online CPG/grocery sales within the next 3 years and challenge many brick & mortar stores and large marketplaces like Instacart.

Let’s dive into this fascinating world of instant commerce.

The Macro

Despite being a relatively new concept for most consumers, the industry is not exactly in its infancy. According to Coresight Research, instant commerce sales in 2021 were estimated to be around $20-25B in the US, equating to a 10-13% share of US online CPG sales.

Another forgotten fact about this industry is that this is not a novel idea either. During the dot com bubble, there were a few companies that attempted this quick commerce concept with Kozmo being at the helm.

Kozmo was founded in 1997 by a couple of investment bankers. It started as a service that delivered videos by bicycle messenger to Manhattan. Their tagline was “from the Internet to your door in under an hour”. It slowly expanded to other items you would usually find in a convenience store and garnered quite some attention from both customers and investors, raising over $250M (equivalent to $400M today). They were profitable in 4 cities but due to massive losses from seven other cities and drying funding, they were forced to shut down 4 years later.

The burst of the dot com bubble put instant commerce on ice for over a decade, until 2013, when GoPuff decided to give it another go. GoPuff started with the college segment and initially focused on hookah delivery before branding out to other convenience store product categories. Gopuff’s revenue grew to over $340M in 2020 at a 40% gross margin.

This industry blew up in the past two years amidst COVID 19. More and more people turned to instant commerce apps as a safe and convenient way to purchase groceries and everyday items.

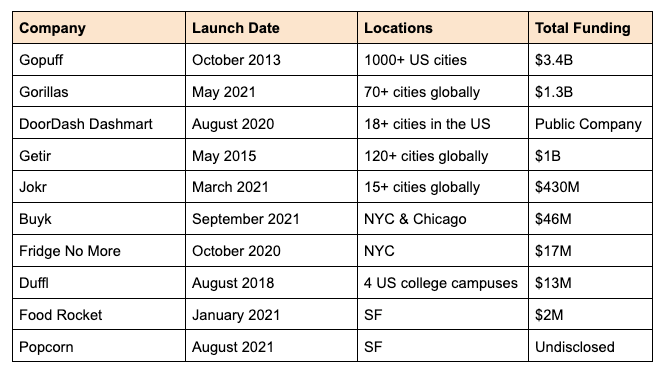

Below is a list (albeit incomplete) of instant commerce players that I have found:

Many heavy-weight venture/growth investors have poured tons of money in the space trying to not miss out on this paradigm shift, for example:

Gorillas - Coatue, DST Global

Jokr - Tiger Global, Balderton, GGV

Fridge No More - Insight Partners

Gopuff - D1, Accel, Softbank

Getir - Sequoia, Tiger

Differentiation

Not all instant commerce startups are built the same. However, before I dive into how different startups in the space are fighting for their competitive advantage, it’s important to first highlight the business model of instant commerce and how it differs from the traditional models, including brick and mortar, supermarket delivery, and marketplace model (e.g. Instacart).

At its core, instant commerce works due to its focus on vertical integration. Companies that operate this model typically do everything in-house, from sourcing products to delivering the order. Some of their unique characteristics include low-fee if not no-fees for consumers, curated but limited SKUs, full-time employees for picking and delivering, and storing inventory in different micro-fulfillment centers (MFCs). Here is a chart by Time Use Institute that compares Instant commerce with other traditional models:

I am not going to talk too much about how instant commerce differs from brick & mortar or supermarket delivery as the chart above does a pretty good job delineating the differences. However, I do want to discuss the nuances between marketplaces and instant commerce since they are both newer models.

Instant commerce vs marketplaces

Marketplace companies use an asset-light approach - they don’t hold inventory and they mostly hire gig workers for picking and delivering. Due to its low fixed cost structure, marketplace startups can very quickly scale to multiple cities and provide a large number of SKUs for consumers to choose from. For example, from July 2020 to July 2021, Instacart scaled its delivery reach from 30,000 stores to nearly 55,000 stores in North America. Marketplace startups’ nimbleness comes at a cost. They don’t have much control over operating hours and stock levels since they rely on third-party suppliers. The bigger issue, however, is that they don’t have strong pricing power over suppliers which results in higher prices for consumers. It’s a common practice for retailers to raise product prices on delivery apps to offset merchant fees.

Instant commerce companies are on the other end of the spectrum. They adopt an asset-heavy model - they rent out warehouses and fulfillment centers, hold inventory, and hire full-time employees for picking and delivering. It’s more challenging and expensive to scale to multiple cities quickly due to the large upfront cost in terms of time and money. However, instant commerce startups have a lot more control over their customer experience and pricing. They can deliver to consumers in under 30 mins due to their proximity to demand and personalize the products that cater to the local preferences. There are also a lot more levers to increase contribution margin in the long run (e.g. private label, volume discount, etc).

Instant commerce 3P2S framework

There are many new entrants in this space. I found that most of them differentiate themselves on five levels.

I call them the 3P2S framework - place, price, personalization, speed, and SKUs.

Place

The easiest way to differentiate one's company is to operate in a region that doesn't have other competitors. For example, while most instant commerce companies focus on large cities like New York, Duffl focuses on college campuses like UCLA and USC. While college campuses might not have over 1M people, they still have the benefit of high population density and strong virality potential.

Price

Another way companies differentiate in this space is the pricing structure. One element of that is the delivery fee. Some companies charge a flat delivery fee such as Gopuff and Gorillas while others do not like Jokr. Delivery fee might not necessarily be the deal breaker if the company can offer a superior value proposition in other areas. Some other pricing structures include minimum order amount, discounts, and more.

Personalization

Due to their hyper-local characteristic, instant commerce companies can personalize the menu to cater to the preference of the specific neighborhood they are serving. For example, they can partner with popular restaurants and niche stores in the neighborhood to offer unique SKUs that consumers won’t be able to find elsewhere. It’s a great way to increase customer stickiness especially as ‘shop local’ continues to be a growing trend.

Speed

Speedy delivery is beautiful.

It’s hard for consumers to go back to next-day delivery after experiencing a 15 mins delivery. Not only is it good for customers, but it is also favorable for the business. Assuming a strong demand, consistent 15 mins delivery allows the company to increase the number of customers it can serve per day, thus increasing its profitability. Instant commerce is a volume game. One SF startup, Popcorn, has an interesting approach for speed. Instead of having MFCs, Popcorn has vans that both store inventory and also deliver. I had a delivery from Popcorn last week that took less than 5 mins 🤯. By using vans as a storage space, they also eliminate the cost of renting out many MFCs.

SKUs

SKUs, aka the number of products on the menu, are another strong differentiating factor. One element that affects SKUs is time. Most instant commerce startups start with a small but curated list of products. Over time, as the customer demand profile is more understood, companies tend to slowly add more SKUs. Customers love more options and more SKUs tend to lead to a higher basket size per order.

Unit Economics Deep Dive

Challenging unit economics is perhaps the most common concern among the naysayers of this industry.

Indeed, without impeccable execution and strong capital backing, it’s extremely difficult to build a profitable business or even just survive the turmoils in the early days. In fact, many instant commerce startups died almost ‘instantly’ due to poor unit economics. One example is 1520, which was an NYC-based instant commerce startup. It raised a big seed round of almost $8M in April 2021 but ceased operation after running out of funding in December. It is now an advertising platform for Getir (another instant commerce player).

Despite the challenges, many leading players in the space have proven that this business model could work. As I mentioned earlier, even Kozmo, an instant commerce startup from the dot com era, was able to obtain profitability in 4 cities even though the internet penetration rate was less than half of that in today’s age. According to an interview on 20 Mins VC, Gopuff has been EBITDA positive since day 1, with a 40% gross margin and a double-digit contribution margin. Its new markets are profitable within 18 months.

Let’s take a look at the economics in the context of two markets - Mexico and the US. The numbers below come from Jokr, one of the leading startups in the space, that operates globally:

As indicated above, the economics differ based on the nature of the market. In Mexico, the basket size tends to be lower due to lower average income. However, it also has lower labor and real estate costs, resulting in an attractive 30-40% contribution margin after picking and delivery. In the US, due to a higher income level, the basket size is bigger, but the cost is even higher, especially for the lease cost. According to the founder of Jokr, Ralf Wenzel, it might be easier to get started in a less expensive market like Mexico and achieve profitability quicker, but in the long run, the profitability remains relatively similar for most markets.

Levers

One advantage of the space is that there are several levers that an instant commerce startup can pull to improve the economics - increase AOV, decrease cost, create new revenue streams. However, several of them do require scale to unlock.

1. Increase average order value

How much people pay per order is mostly determined by the products on the menu. One way to do so is to expand product categories. According to Turner Novak in his Jokr deep dive, the total basket size doubled for Jokr’s April cohort in just 5 months after the company expanded its categories and SKUs count significantly.

Demand prediction is also key. It is important to have a systematic approach to product expansion by considering not only the consumer preference but also the potential order frequency and complexity of holding that inventory.

Postmates has a great framework for product expansion:

2. Decrease cost

There are three main cost drivers in this business - real estate cost, COGS, and delivery cost.

There is not much you can do with real estate, the market you choose determines the price. You have to choose an area with enough population density and according to the founder of Food Rocket, “in order for the business to work, stores need to be set up in locations where its limited delivery radius can cover 50,000 homes”. Well… most of those places with that high of a population density tend to have a high leasing cost.

There are more ways to decrease COGS. The biggest one is to set up an effective procurement infrastructure that allows the company to procure efficiently from local suppliers and farmers and only procure the right products at the right time to minimize inventory waste. Another approach to decrease COGS is offering private label products. According to Ralf, private labels could make sense for certain product SKUs and increase the margin by an additional 5-10%.

Finally, to decrease the delivery cost, the key is to create an effective delivery infrastructure, such as creating a better routing algorithm or batching orders together in one ride. There is a special metric in the industry called ODH (orders per rider per hour). It is also a proxy for the profitability of a market. According to Gopuff, the market becomes profitable once ODH is over 4.

3. Create additional revenue streams

There are a lot more revenue opportunities once the instant commerce company reaches scale. One opportunity is ads. Since instant commerce is hyper-local, it has very targeted groups of customers, which can be very valuable for advertisers. Another opportunity lies in sampling. Instant commerce companies can help CPGs brands like Pepsi to test out their new products, and in return, CPG brands have to donate inventory and pay sampling fees.

Challenges and Predictions

I am a fan of the instant commerce model since it provides a better value proposition for consumers (fast delivery and low fees). However, as I alluded to earlier, it can be quite challenging for startups to withstand the turmoils in the early days. This model only works if there is enough scale (# of orders) to offset all the fixed costs.

Companies have to endure heavy losses in the beginning and sprint to get to positive unit economics while praying that cash doesn’t run out in the meantime. It is particularly difficult in major cities like New York, where all the VC-backed startups are throwing money at consumers to reach scale. Consumers are also incentivized to experiment with multiple instant commerce apps to find the best discounts and prices. As a result, I predict that most of the small or medium players won’t be able to get to the other side before funding dries out.

The current environment also reminds me of what happened during the early days of the ride-hailing battle. One thing we can learn from that period is that consolidations are likely to happen when companies are competing on similar value props in the same cities. The Information reported on Monday that Jokr is in talks to sell its New York operations as losses continue to mount. Jokr’s investors want the team to focus on Latin America, a cheaper market to reach that coveted scale. As the public equity market continues to get hammered, which has also affected fundraising in the private market, conserving cash is becoming more and more important. Similar consolidations have happened around markets outside of the US as well. For example, to push for the UK market, Getir acquired its UK competitor Weezy and Gopuff acquired Fancy and Dija.

It’s too early to tell who will be the winners in this space but due to the size of the market, there could be several instant commerce players that co-exist with similar dynamics as the food delivery space.

Which instant commerce startups do you like the most? Please reply because I would love to hear from you!

See you soon 🤙,

Leo